The mini-budget, house prices and me

Talk is cheap, but is it the truth

The three questions I am asked most are: When will house prices fall? By how much will they fall? and By how much will the price of my house fall?

I was at an event for estate agents earlier this week and the feeling, behind the closed doors, even in that room, was that house prices are about to fall.

It seems to me that we are trying to talk ourselves into a downturn, with the more ardent bears seeing a house price crash as a foregone conclusion. However, the problem with doomsaying is that we tend to overestimate the frequency of bad events. Even the Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Samuelson joked that: “Economists have predicted nine of the last five recessions”.

In this article, we look at what the mini-budget might mean for house prices

The mini-budget

The mini-budget was mini only in name. It amounted to the largest tax cut in 50 years and set out the Truss Government’s desire for the UK to grow its way out of its current economic challenges. The details of the budget have been widely reported elsewhere, but after offering support for energy bills, the thrust was tax cuts. Cut National Insurance, cut Income Tax, cut Stamp Duty.

The big-gamble

Inflation is rampant in our economy, and to be fair to the UK Government there are external and global factors at play, but the mini-budget put all bets on growth.

The big gamble is that economic growth will outpace inflation and that growing the size of the pie will temper the price of the pie.

The big gamble is to fight fire with fire and release more money into the economy with the hope of stimulating the supply of goods and services more than the price of goods and services

Actions speaking louder than words?

Early in his speech Kwasi Kwarteng said that he remained closely coordinated with the Bank of England, and was speaking to the Governor twice a week. However is this a case of actions speaking louder than words with the Chancellor seeking to stimulate economic demand whilst the Bank of England is working hard to constrain it? If the Chancellor is true to his word about the sacrosanctity of the Bank of England’s independence, will we see a battle royale between the Governor and the Chancellor, with tax cuts being the weapon of choice for one and rising interest rates for the other?

Will the mini-budget have a big impact on house prices?

First a health warning. Many would regard me as a bull on house prices. It is fair to say that I tend to view glasses as half full rather than as half empty, but I am not a perma-bull. I should also point out that I have got house price predictions wrong in the past and I am sure I will also get them wrong in the future.

At the start of the credit crunch, I predicted that house prices would fall by 30% to reach a benchmark level of affordability. I was wrong. House prices fell by 19% and then started going back up.

When the Government effectively closed the housing market in May 2020, I predicted that, at best, house prices would be flat. I was wrong. Since May 2020 the Halifax house price index has increased by 23% and the Nationwide House Price Index by 25%. It seems that at times I too have joined the ranks of the trigger-happy doomsayers.

Lessons from the Global Financial Crisis

Before its upgrade to the Global Financial Crisis, it was known as the credit crunch. Credit was crunched. Banks stopped lending or required huge deposits to sign off a mortgage. Homebuyers did not have the big deposits required, and housing transactions and house prices fell.

House prices and housing transactions started to rise again as the banks started to lend again. In my view, banks were one of the main drivers of both the downward and upward movement in house prices.

Banks are in the business of lending money; it pains them not to lend. Deep down no one wants to be invested in, work in or manage a shrinking business. A bank not wanting to lend is akin to an estate agent not wanting to sell a house.

Lesson learnt: Banks want to lend

Lessons from lockdown

I have yet to find anyone who thought a pandemic and three lockdowns would be good for the housing market and usher in a period of rapid house price growth, and I suspect that the vocal bears today have been champing at the bit to talk down the housing market since the pandemic struck.

Homebuyers are emotional rather than rational. Classical economics is based on the assumption that we act as rational beings, the growing and Nobel prize-winning area of Behavioural economics is based on the assumption that we are not rational. Few if any of us are rational.

During the pandemic stamp duty holiday, a rational homebuyer would have taken the stamp duty saving and added it to their homebuying budget, increasing the amount they could offer to purchase their next home. I remember having debates with other housing market professionals about how the ‘saving’ would be shared between buyer and seller. We were in the biggest and deepest global recession in history facing a disease with no known cure, not the most supportive backdrop for a bull market.

When the Stamp Duty holiday was announced the average stamp duty saving was £2,200. By the end of the Stamp Duty holiday house prices had increased, on average, by £35,200 or 16 times the amount of the stamp duty saving. Homebuyers were £33,000 worse off.

House prices were not rational, but why should they be the households buying the homes aren’t rational either?

The bears are rational, they will talk about stretched affordability and rising living costs and increasing mortgage rates, but what we learnt from lockdown is that whilst the bears might be rational, the housing market is not.

Lesson learnt homebuyers are not rational. Once a homebuyer has found the home they want to buy, emotions trump rationality, we all know that because we have all been there either with a home, a holiday, or a potential partner.

Back to the mini-budget

The Government believes that:

Doubling the nil-rate band will enable up to 29,000 more people to move home each year, in turn boosting household consumption, which will increase confidence in the economy and support the hundreds of thousands of jobs and businesses which rely on the property market. This includes, for example, estate agents, cleaners, builders, contractors, removals companies, plumbers, decorators and others

No doubt the 29,000 was calculated by a highly educated and rational member of the Chancellor’s team using logic and a spreadsheet. I suspect that no behavioural economists were asked to help arrive at this figure.

In my view, the Government has used a rational process to calculate the emotional impact of a policy decision.

My initial thought when I learned of the stamp duty cut was will the benefit of the saving be swallowed by the impact of rising mortgage rates. Will it, therefore, have any impact at all? In a rational world probably not, but in the real world it probably will, time will tell.

And so to House prices…

We have learnt that banks like to lend, and we like to buy houses. Many suggest many of the problems we have today are due to our reliance on oil. Western economies are built on oil and run on oil (and its derivatives) and rely on oil. There are a lot of vested interests in oil

Perhaps house prices are similar to oil. Banks have a vested interest in house prices going up, they use the value of homes as security on their loans, the more loans they can make the bigger profits they make. The more security they have the more loans they can make. If house prices fall it creates a lot of problems for banks.

Politicians like house prices to go up. Homes are most people’s biggest asset and when house prices are rising, voters are happy, and happy voters tend to vote for the politicians who helped house prices rise, and whilst the majority of voters are homeowners politicians will seek to keep homeowners happy.

The UK has a pension crisis. The average adult retires with a pension pot of around £65,000, but the sane retiree probably lives in a mortgage-free property worth around £250,000. The value tied up in our nation’s homes is key to funding the retirement plans of our ageing population.

Inflation friend or foe?

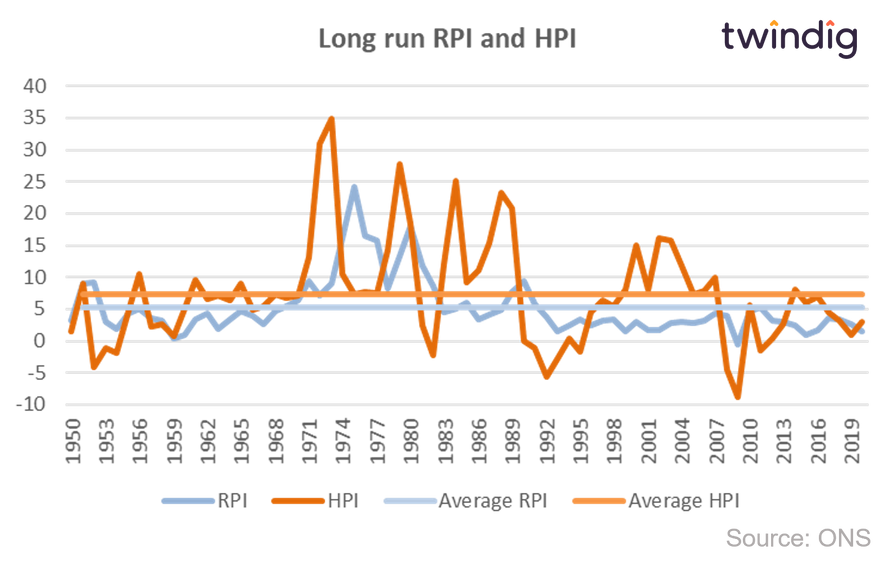

We need inflation for a healthy economy. If we all thought we could buy everything cheaper tomorrow we would wait and the economy would stall. Periods of inflation are usually followed by periods of rising wages, if not we would all get poorer, not richer. Mortgages are based on a multiple of our wages. If inflation leads to rising wages, it will also lead to bigger mortgages which will lead to higher house prices.

Conclusion

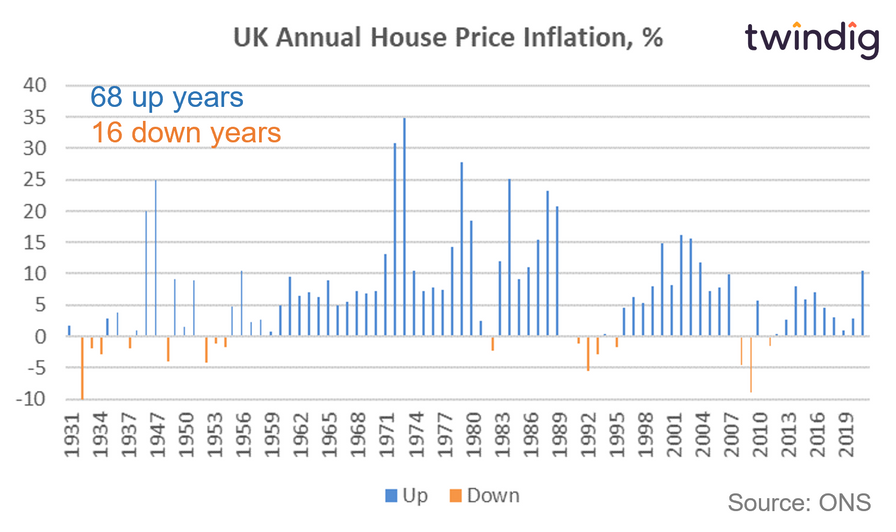

I cannot answer the three questions I am asked most frequently with any accuracy, but I can leave you with two charts that view the house price glass as half full. The first shows that house prices go up more often than they fall. The second shows that house price inflation tends to outstrip underlying inflation.