Fixing the housing market ladder: Part 1 - Help more to buy

The UK housing ladder is broken at both ends.

First-time buyers need a helping hand to step onto the housing ladder and older households need a hand to access the housing wealth they have accumulated.

This article looks at how a bigger bolder version of help to buy could repair the broken lower rungs of the housing ladder.

Setting the scene: UK Housing market dynamics

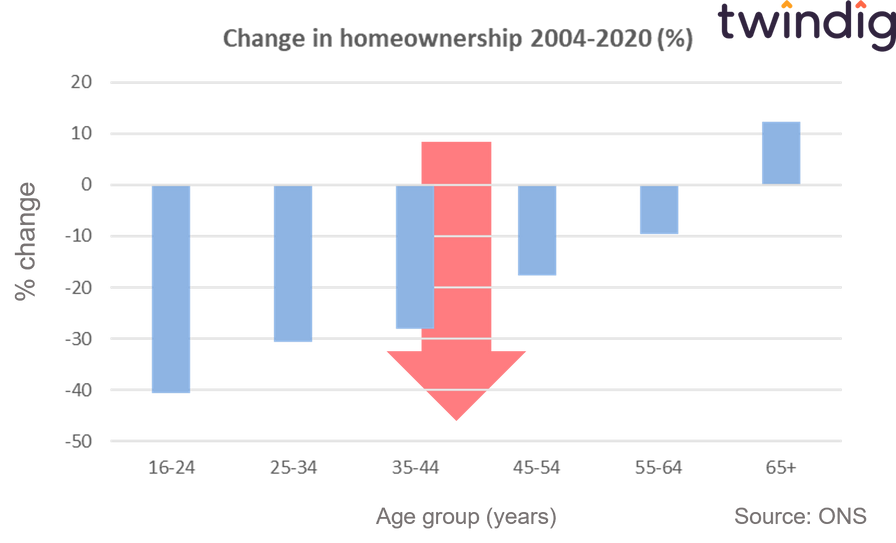

Homeownership is falling across all age groups, apart from those aged 65 and over

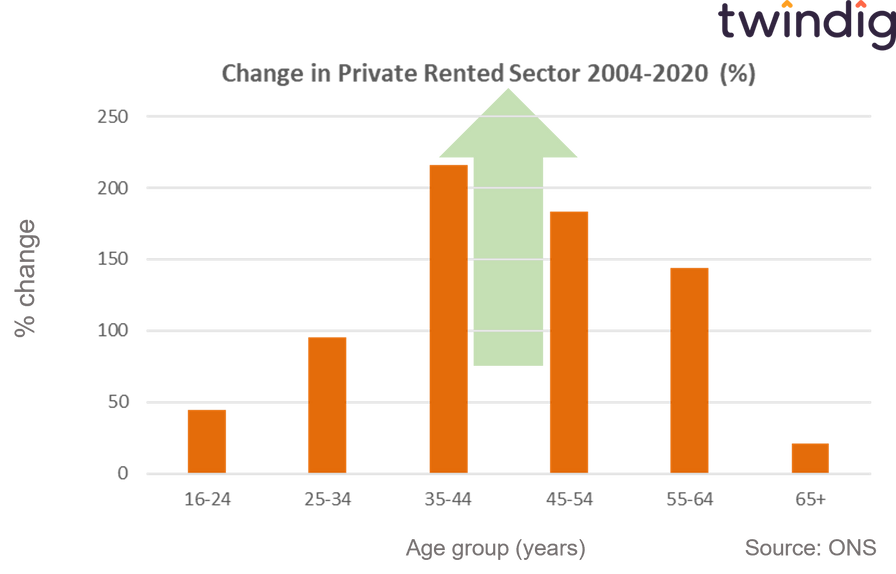

Meanwhile, the private rented sector continues to grow, with growth rates accelerating in the 35-64 years age groups

But is renting a lifestyle choice?

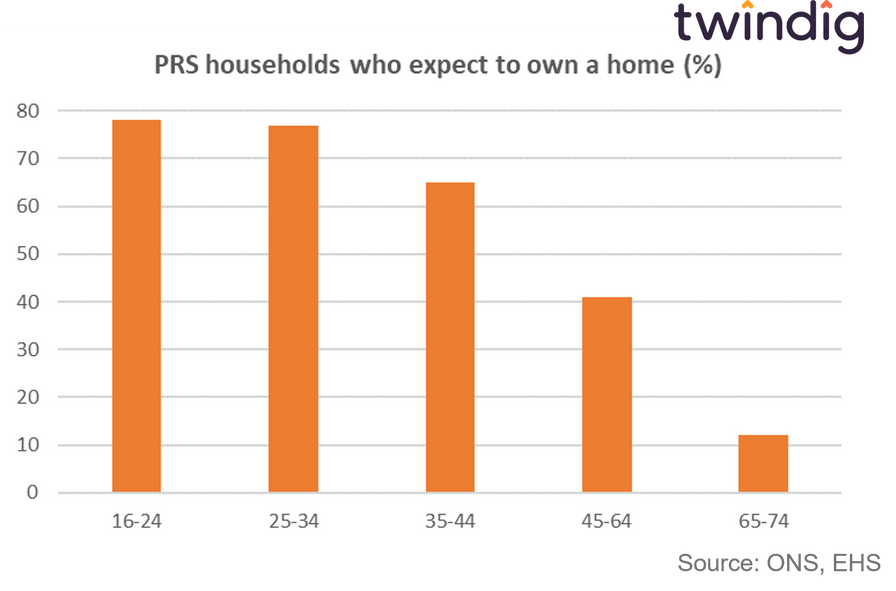

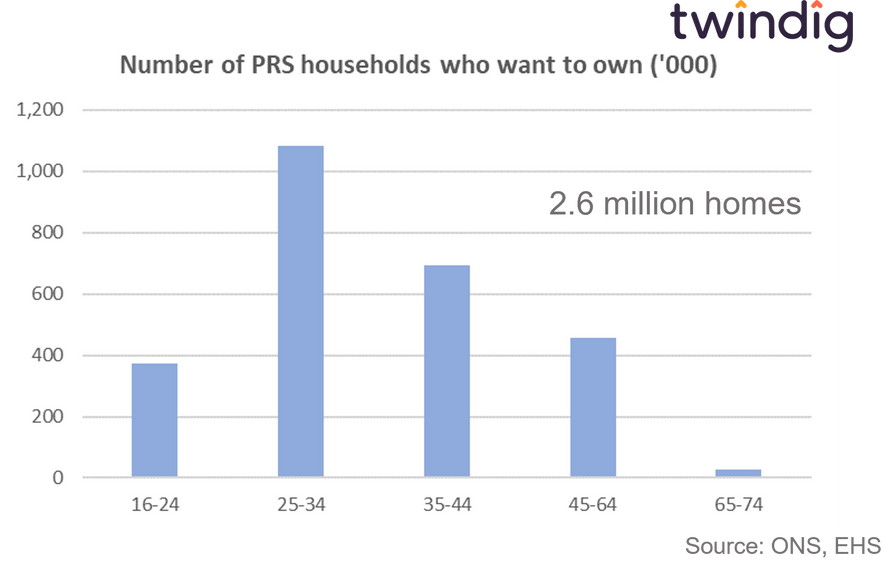

Some believe the changing tenure patterns reflect a lifestyle choice, where an increasing number of households choose the flexibility of renting over the rigidity of buying. We disagree, and so it seems, do the majority of those living in private rented accommodation.

Neither the Credit Crunch nor the COVID crisis has dented renters desire to buy a home. According to the latest English Housing Survey almost 80% of those aged 16-34 years old in the private rented sector expect to own their own home in the future. That equates to around 1,500,000 households.

Across the private rented sector as a whole, 2.6 million of 60% of households aspire to own their own homes, but that dream continues to disappear as the barriers to homeownership.

The barriers to homeownership are rising

The issue is a simple one. House prices are rising faster than wages. In our view, house prices have become divorced from wages. Very few have a high enough income to generate the mortgage multiple they need to buy a home. The gap between house prices and mortgage capacity is filled by the deposit.

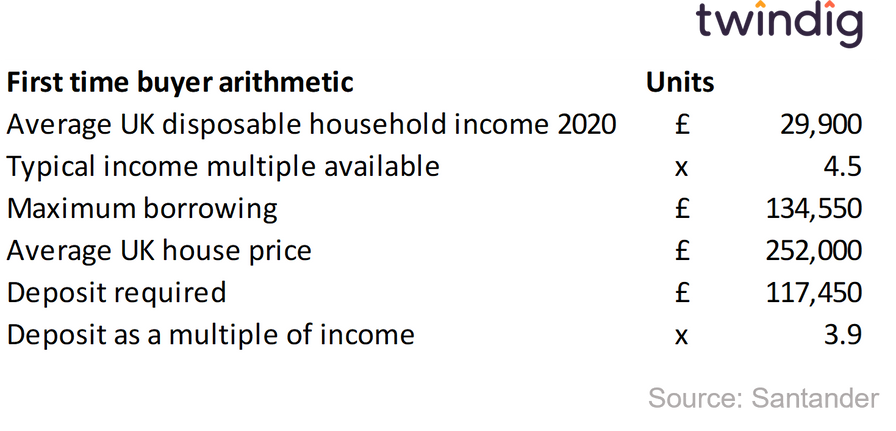

Santander’s report Life After Lockdown clearly highlights the deposit barrier. They reported that the average UK household with a disposable income of £29,900 would need a deposit of £117,450 to buy the averagely priced UK house for £252,000.

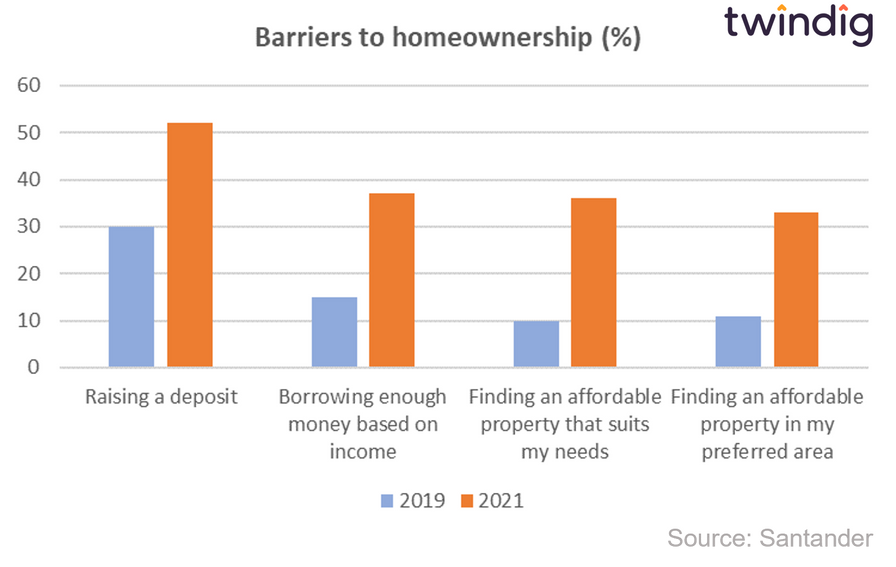

Santander’s report went onto highlight that raising a deposit was the largest barrier to homeownership before the pandemic and is an even bigger barrier as a result of the pandemic.

How did we build these barriers?

It has been said that the road to ruin is paved with good intentions, and we believe that the same can be said about the problems facing the UK housing market – they are caused by walking along a road paved with good intentions.

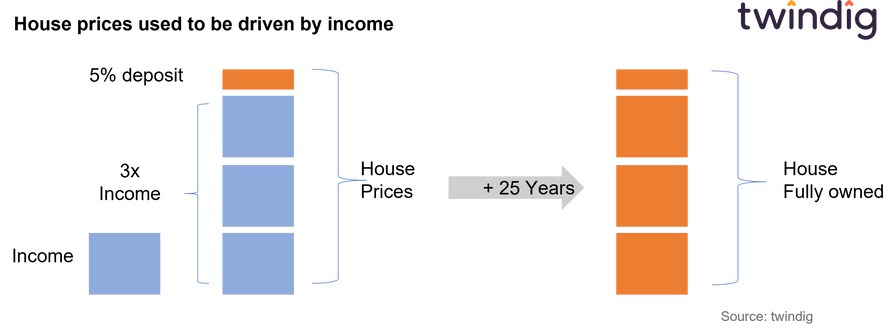

House prices were initially linked to income

House prices used to be a function of income plus a small deposit. Lenders liked to see a homebuyer have some skin in the game and to protect themselves from some of the risks connected to falling house prices.

This system worked very well, but in our view, the problems facing the housing market today can be traced back to 1971.

So what happened 50 years ago?

The UK Census in 1971 reported that homeownership had reached 50%, for the first time we had become a nation of homeowners.

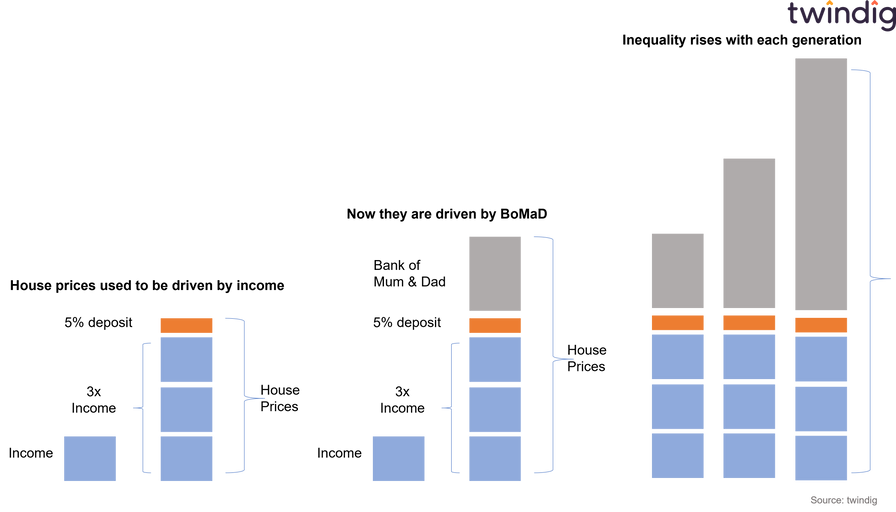

We are therefore now seeing the first wave of mass affluent (UK homeowners) passing on their housing wealth to the next generation.

It is our view that wealth accumulated in housing stays in housing. Bank of Mum and Dad often release equity to provide the equity for their children/grandchildren, and we believe that homes that are inherited are normally sold with and the proceeds used either to pay off an existing mortgage or to assist a move to a bigger house.

With every generation, the amount of wealth invested in the housing market grows, and buying a home becomes more about how much wealth your family has than how much you earn. We believe it is these intergenerational wealth transfers that have led to the divorce between house prices and incomes.

Family vs society

What starts as a good intention and a logical pattern of behaviour at the family level has drastic and far-reaching consequences at a society level, shutting those without access to the bank of mum and dad out of the housing market and accelerating the increase in inequality of housing wealth.

Is the answer to reduce house prices?

Yes and no. Yes, if house prices fell enough to re-tie them to wages that would help first-time buyers, but many more would see their wealth destroyed by negative equity, which would cause them and the providers of their mortgages significant problems. Significant house price falls also hurt most those who have most recently bought. If you are aged 65, mortgage-free and have seen the value of your home increase by multiple times then a 25% fall in house prices is unwelcome but not life-changing. Whereas if you purchased a home 3 years ago with a 95% mortgage a 25% fall in house prices could very well change the pattern of your life.

Reducing house prices is harder than you think it is

Homeowners spend a lot of time worrying about house prices and many who have purchased during the stamp duty holiday are wondering if, in the heat of battle, they paid over the odds, but house prices are stubbornly robust.

If ever there was a time for a large-scale resetting of house prices it was during the Global Financial Crisis, which, with hindsight, came after a period of very lax mortgage lending practices (lending practices were significantly tightened by the 2014 Mortgage Market Review).

Rampant house price inflation

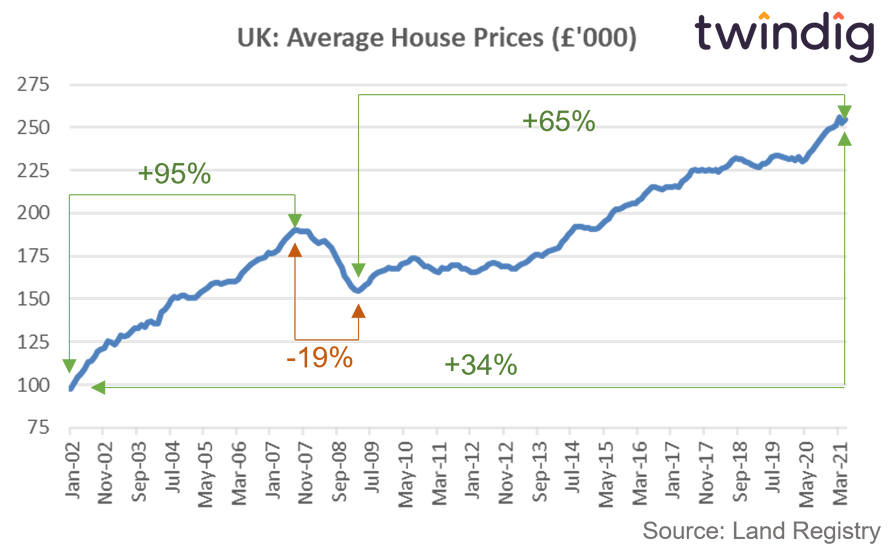

Between January 2002 and the pre-global financial crisis peak in September 2007 average UK house prices almost doubled, increasing by 95% from £97,600 to £190,000.

A minor correction

House prices troughed in March 2009 at £154,500 a fall of 19%

A major rise

Since the house price trough in March 2009 house prices (as of May 2021) have risen by 65% to £254,600 a figure 34% higher than their pre-credit crunch peak.

Conclusion

Reducing house prices is harder than you think

The solution: Help people to buy a home

The Government-backed Help to Buy scheme has both supporters and detractors. The supporters say it helps aspiring homeowners onto the housing ladder, the detractors that it pumps more money into the housing market and by adding more fuel to the fire it stokes up house prices.

Does Help to Buy stoke house prices?

Help to Buy was launched in Q2 of 2013 and by the end of 2020, it had helped 313,000 households in England and Wales buy a home. Over the same period, there were 6.85 million housing transactions across England and Wales, implying that help to buy accounted for less than 5% of housing transactions.

Meanwhile, over the same period, there were 4.2 million deaths in England and Wales, of which 68% or 2.8 million were aged 75 years and above. Homeownership rates for those aged 65 and over were 78% between 2013 and 2020. This implies that up to 2.2 million homes were inherited over the same period a figure which far outweighs the number of households helped by help to buy especially if any inheritance was split between more than one person. Even if we assume that half of those deaths did not lead to an intergenerational inheritance, the number inherited (1.1 million) is still 3.5x higher than the number of homes purchased with the assistance of help to buy.

So, to answer the question: Does help to buy stoke up house prices? Help to buy is less than 5% of housing transactions and in our view unlikely to move the whole market, and even if it was inflationary, it is unlikely to be as inflationary as the impact of households inheriting housing wealth, in our view.

Help ‘Help-to-buy’ be bigger

In our view, now that house prices have been divorced from wages, it is very unlikely that the two can be reconciled and a relationship re-established, especially given the scale of intergenerational housing wealth transfers.

We have also noted that house prices remain stubbornly high, even when subjected to a global financial crisis, a meaningful correction of house prices did not occur. The robustness of house prices no doubt reflects the equity richness of the underlying assets. The UK housing market has a value of more than £7 trillion and an overall loan-to-value of around 16% (Debt c.£1bn Equity c.£6bn).

We view homeownership as a social good because if housing wealth can be accumulated over the early and middle stages of life, it can be used to help fund the later stages of life.

However, without access to the bank of mum and dad homeownership is increasingly out of reach and intergenerational housing wealth transfers will, in our view, lead to an escalating level of housing wealth inequality.

Help to buy for the whole market, not just new build

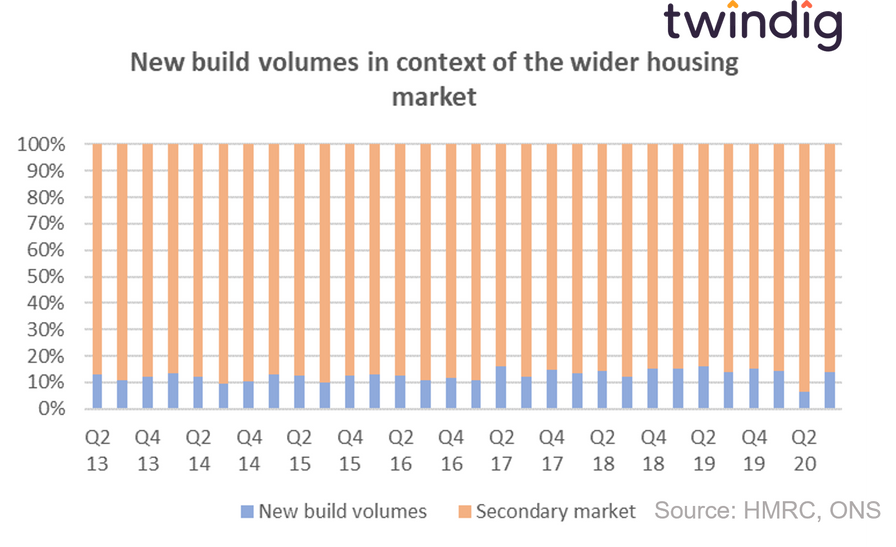

The New build market accounts for around 15% of housing transactions, and about one in three new build transactions are completed with the assistance of help to buy.

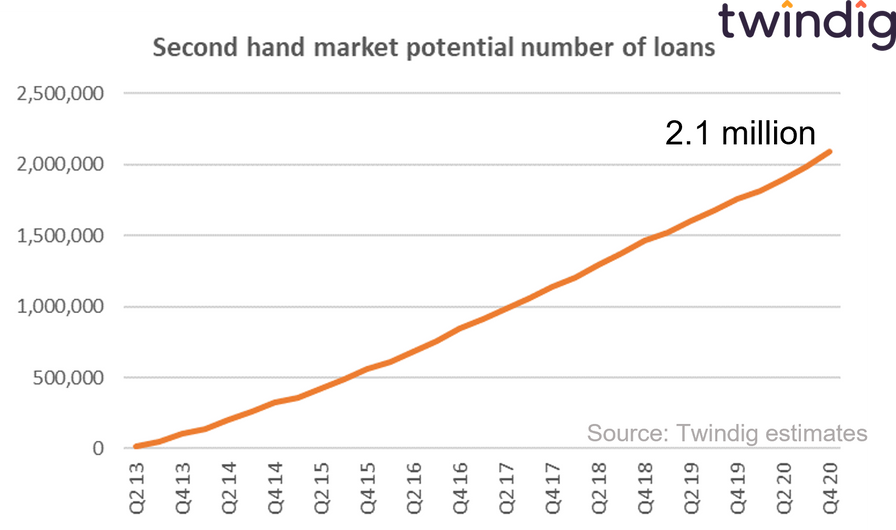

If help to buy had been offered to the whole market and the take up followed the same pattern as with new build it could have helped 2.1 million households buy their home.

How would this be funded?

The good news is that we believe help to buy for the second-hand market could be funded without help from the taxpayer.

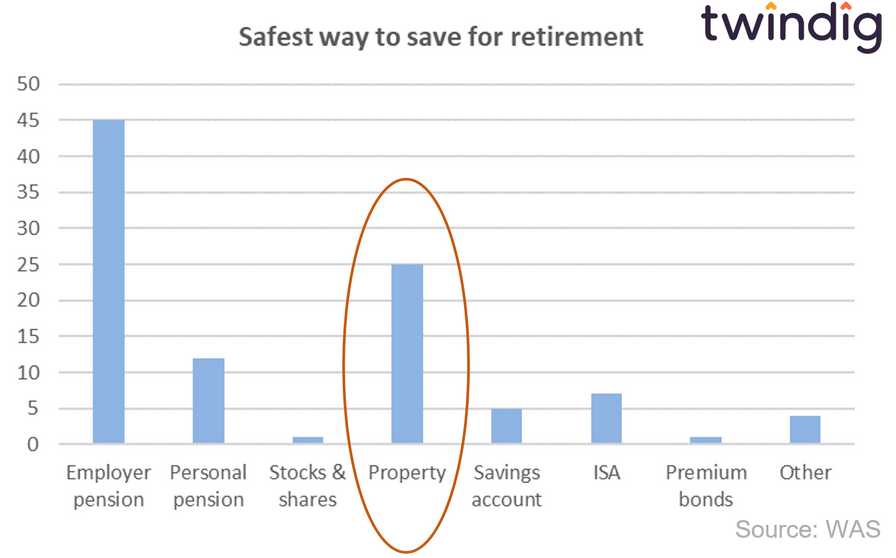

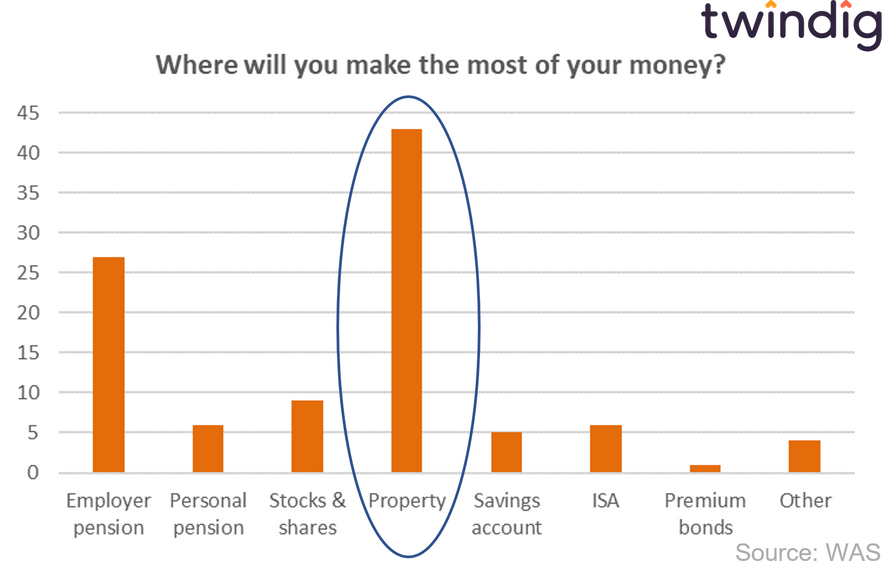

The Government’s wealth and asset survey consistently reveals that adults in the UK view property as an important way to save for their retirement, second only to an employers pension scheme.

The Wealth and Assets Survey also shows that UK adults believe that returns from property will be higher than the returns they get from an employer's pension.

However, aside from directly buying an entire property, there are very few ways to get access to the UK housing market.

We believe that setting up an investment vehicle for an existing homes market help to buy scheme would provide three main benefits

It would help more aspiring homeowners take their first step on the housing ladder

It would provide an opportunity for UK adults to directly invest in the UK housing market (via ISAs and pensions) without the need to buy a home outright

It would provide a property market-linked investment vehicle to help aspiring homeowners (and/or their parents and grandparents) save for their deposit, which would rise and fall in line with the asset they are seeking to buy.

Wouldn't such an investment be illiquid?

No, not in the way we are thinking of structuring it... but more on that in another article...